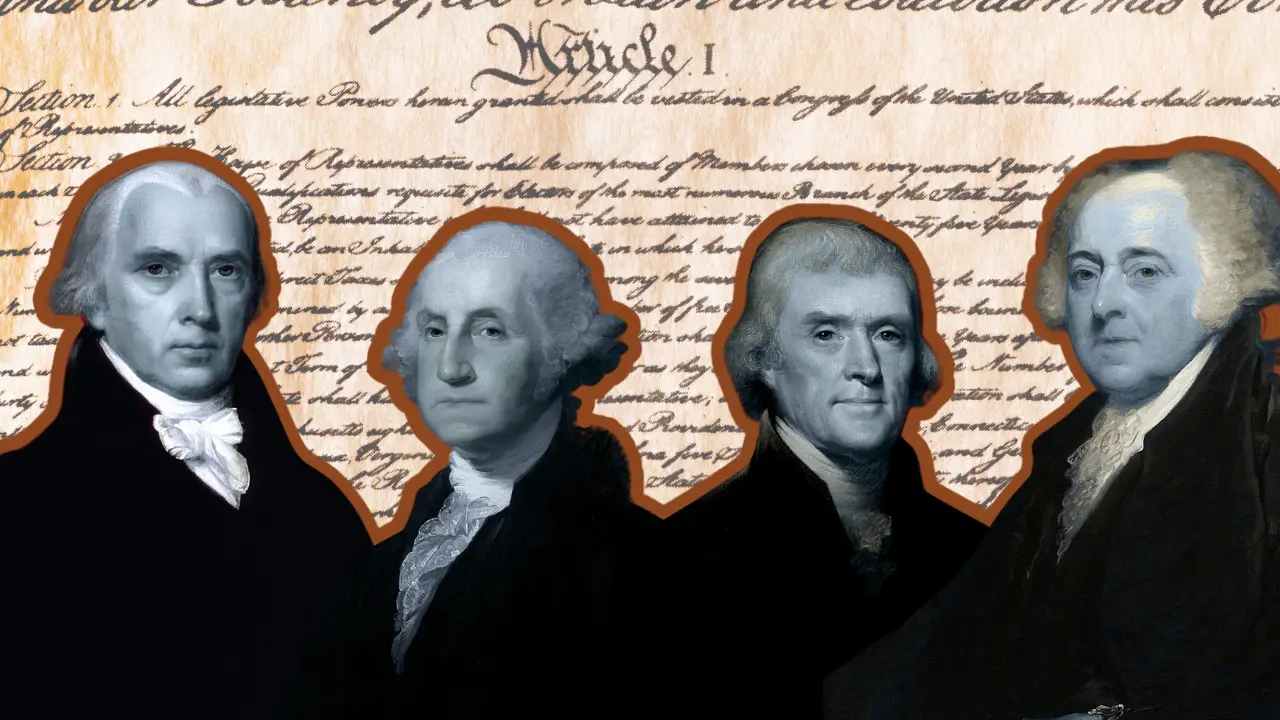

Writing a Republic: The Founding Fathers and the Fight for a Constitution

A Fractured Start and the Urgency to Rebuild

The ink on the Declaration of Independence had barely dried before the young nation began unraveling. The Articles of Confederation—hastily written and hopelessly weak—left the states floating in a sea of disunion. There was no executive branch. No real judiciary. And Congress? Powerless to tax, toothless to enforce. It was less a government than a polite suggestion.

So, when delegates gathered in Philadelphia during the brutal summer of 1787, it wasn’t just about legal theory. It was survival.

And for many, particularly Black Americans reflecting on that chapter, the paradox is hard to ignore: fighting for freedom while denying it to so many. Still, that flawed gathering gave birth to a document that would—eventually—hold enough power to challenge even its own contradictions.

Breaking the Silence: Why Black-Owned Media Was Born Out of Necessity

It wasn’t ambition alone that birthed the Black press. It was survival.

In a time when lynchings made headlines—if they were mentioned at all—with barely a whisper of justice, Black Americans needed their own chroniclers. Their own gatekeepers. Their own architects of narrative.

The white press didn’t just omit. It distorted. Stories about Black life were filtered through a lens so cracked and crooked, it twisted tragedy into entertainment and resistance into threat.

So, Black visionaries did what Black visionaries always do: they built.

They didn’t wait to be invited to someone else’s newsroom—they created their own printing presses, often in back rooms, basements, and borrowed spaces.

Black newspapers didn’t merely fill gaps; they dismantled lies.

Where the mainstream portrayed Black communities as impoverished, dangerous, or apathetic, these publications showcased Black excellence. They wrote about business owners, artists, inventors, teachers—people with dignity and ambition, not just struggle and pain.

They corrected the record. And more importantly, they reframed the lens.

Whether calling out hypocrisy in political speeches or spotlighting neighborhood heroes, Black newspapers laid the groundwork for reshaping how Black life was seen—and understood.

James Madison: Quiet Genius with a Vision

Photo from www.britannica.com

He was small in stature, often anxious, and plagued by chronic illness. But James Madison didn’t need to raise his voice to command respect. His intellect did that for him.

He came to Philadelphia with more than ideas. He brought a full draft. The Virginia Plan was bold: a national government with three branches and a system of representation that favored populous states.

Some thought it arrogant. Others saw brilliance. Madison knew one thing: without structure, liberty couldn’t last. His mind was wired for balance—ambition counteracting ambition, power dispersed across carefully drawn lines. Even his detractors admitted the man saw further than most. Today, he’s rightly called the Father of the Constitution.

George Washington: Presence as Power

Washington didn’t need to say much. Just being in the room elevated the proceedings. The war hero hadn’t asked to be president of the Convention. In fact, he’d hoped to retire for good. But when the republic asked, he answered.

His leadership provided calm during stormy debates. He didn’t weigh in often, but when he did, people listened. Washington wasn’t a theorist like Madison, but he understood something crucial: America needed legitimacy. And his name brought it.

Franklin and Hamilton: Contrasts in Drive and Diplomacy

Benjamin Franklin arrived in Philadelphia old, ill, and carried by convoys through the city streets. But age hadn’t dulled his instincts. His wit still cut sharp, and his timing—always impeccable. He didn’t speak often during the Convention, but when he did, people listened. Franklin was the balancer, the peacemaker, the quiet center of a storm full of younger, louder ambitions.

When tempers flared and the room split into factions, he leaned in with a story or a pointed observation—never scolding, always guiding. When compromise seemed out of reach, he helped shape it, reminding the delegates, in his way, that unity wasn’t a luxury. It was the only way forward.

Alexander Hamilton, on the other hand, stormed into every debate with fierce energy. Born in the Caribbean, self-made, and endlessly ambitious, Hamilton had little patience for what he saw as inefficiency. He wanted a strong central government—a system that could defend itself, command respect, and move fast.

Hamilton didn’t get everything he wanted. But he moved the needle forward. And he wrote like lightning.

Thomas Jefferson: Absent but Not Silent

Jefferson wasn’t at the Convention. He was in Paris, serving as a diplomat. But his ideas hovered over every word. The principles he’d etched into the Declaration still loomed large: liberty, equality, and the rights of the governed.

He corresponded frequently with Madison, questioning and challenging from afar. Jefferson was suspicious of centralized power, wary of elites drafting rules without broader input. He would later become a champion for adding a Bill of Rights—a move that fundamentally shaped the document’s legacy.

The Fight for Ratification: Convincing a Wary Public

Photo by Mona Eendra on unsplash.com

Writing the Constitution was only half the battle. Selling it? That was war.

Many Americans distrusted the proposed system. They feared tyranny in a new form—an elite government that might one day mirror the monarchy they had just escaped. Farmers, laborers, and tradesmen wanted guarantees. They wanted protection from centralized overreach.

Public meetings turned heated. Pamphlets and essays flooded cities and towns. It wasn’t just about structure anymore. It was about identity.

Federalists vs. Anti-Federalists: The Nation Splits

Federalists, led by Hamilton, Madison, and John Jay, argued that the Constitution would bring stability. A strong national government, they said, wasn’t a threat—it was a necessity. Without it, the union would fall apart

Image by www.freepik.com

Anti-Federalists pushed back, hard. They feared a distant ruling class, unaccountable to the people. Their critiques weren’t empty. They asked what would become of individual rights, of local voices, of the balance they fought a revolution to win.

The debates weren’t polite. They were fierce, personal, and shaped in coffeehouses, churches, and newspapers. The country held its breath.

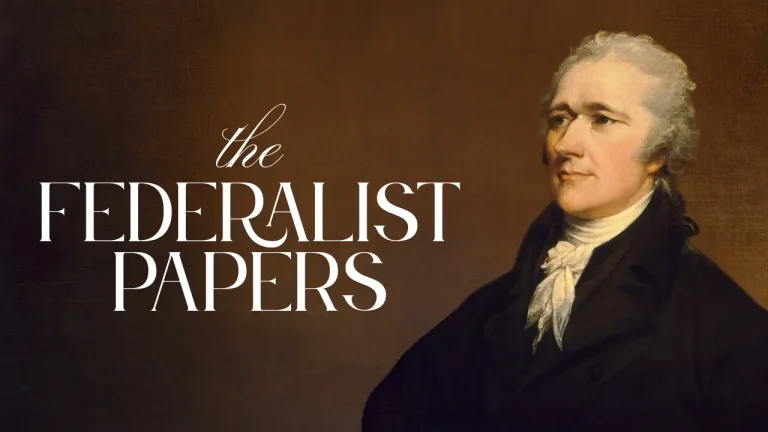

The Federalist Papers: Essays That Turned the Tide

Hamilton, Madison, and Jay took to their pens. Writing under the pseudonym “Publius,” they published 85 essays that explained, justified, and defended the Constitution line by line.

The essays didn’t just argue. They educated. They transformed skepticism into cautious support. They laid bare the rationale behind each clause, turning abstract governance into a clear, practical vision.

Even now, The Federalist Papers remain a masterclass in political persuasion.

One State at a Time: Narrow Margins, Massive Stakes

Ratification wasn’t unanimous. Some states passed it by razor-thin margins. In places like Massachusetts and New York, the vote was a cliffhanger. It came down to town debates and individual speeches. Families split. Communities wrestled.

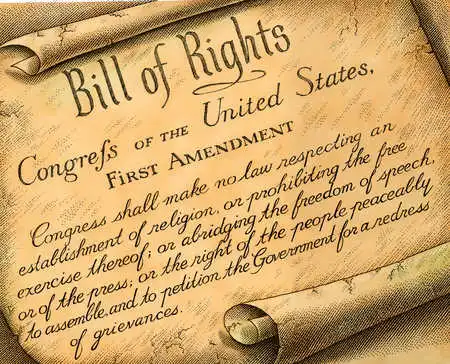

Ultimately, a compromise saved the Constitution: the promise of a Bill of Rights.

The Bill of Rights: Securing the People’s Liberty

The first ten amendments weren’t afterthoughts. They were lifelines. Protections for speech, religion, the press, assembly, and the right to bear arms. Protections against unlawful searches, cruel punishments, and unchecked authority.

They answered the cry of Anti-Federalists and reassured a nervous public.

For Black Americans, these rights would take generations to materialize—and still face threats today. But the framework to demand them was finally written.

Madison’s Evolution: From Centralist to Champion of Rights

Madison, once wary of enumerating rights, changed course. He listened. He adapted. His pivot wasn’t weakness—it was wisdom. He recognized that a republic must serve its people visibly, not just in theory.

So he authored most of the Bill of Rights himself, proving that even the authors of the Constitution could be moved by the public they served.

Legacy of the Constitution: Still in the Room With Us

The Constitution isn’t frozen in 1787. It lives. It argues. It evolves.

Every modern debate—about voting rights, surveillance, equal protection, or executive power—traces back to that parchment. That blueprint. That fight.

And while the Constitution was born in contradiction, it contains within it the tools for course correction.

For Black professionals navigating the complexities of law, leadership, and legacy today, the Founders’ fight offers a mirror and a challenge.

The Constitution doesn’t guarantee justice. But it offers a platform to demand it.

And that may be its most radical promise of all.

More News /Article

- "Don't muck it up" : Massie urges Senate to pass Epstein bill as House vote looms

- Watch live: Trump meets with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman at White House

- Epstein battle ‘has ripped MAGA apart,’ Marjorie Taylor Greene says

- Brian Walshe pleads guilty to lesser charges related to death of his wife as murder trial is set to begin